I have attended the Oregon Book Awards for years. I love being in the Gerding Theater when it’s packed with other people who love stories and who understand what it takes to create a life of words.

I was thrilled when THE WAY BACK FROM BROKEN was selected as a finalist for the young adult literature award. And of course, as the awards ceremony approached, I thought about winning. I wanted to stand on the stage and be acknowledged as a valued member of the Oregon writing community. I wanted to get a little more love for a book that hasn’t sold as well as I had hoped. And most of all I wanted to share it with the family and friends that have been in the trenches with me.

When the awards ceremony finally rolled around, I was nervous. I picked my outfit careful. I invited my people, who came in a rowdy, optimistic crowd. I wrote a speech. My anxiety was subtle but present. I wanted the book to be recognized, and I feared that if it weren’t then I might somehow think less of my own work.

As it turned out, I did not win.

Was I disappointed? Yes. Not a lot, but a little. It never feels good to be passed over. It always hurts a little to have your work judged and found wanting. So yeah, I felt a little bad, and I worried about letting down my family and friends who came to the awards ceremony ready to cheer for me.

But the next day, I visited a class at one of Portland’s alternative high schools. The students had just finished a unit based on THE WAY BACK FROM BROKEN. We had a really good conversation about the book. These teens, whose lives are anything but easy, connected to Rakmen and his story. They got what I was trying to do. And this ultimately is what really matters to me—that a reader who needs a story like this finds it.

I didn’t win, but losing didn’t make me feel any different about my book. I wrote the book I need to write and I put it out into the world. That feels like an accomplishment. So in honor of that, I’m going to share with you the speech I wrote but did not get to give on the stage at the Gerding. I mean every word of it.

I wrote a book about the saddest, hardest thing that ever happened to me—the death of my daughter, Esther Rose. It took 10 years to be ready to write it. It took me another five to actually write it.

That I’m standing here, that I survived much less that I wrote a book is a testament to those who held space for my grief as well as my writing: my husband, my parents, my other children, my writing group, my closest friends, my agent. Most of them are here tonight.

I don’t believe that everything happens for a reason, but I do believe it was my moral responsibility to make meaning out of tragedy. THE WAY BACK FROM BROKEN contains everything I know about grief and loss and the healing power of wilderness.

It turned out that the writing of this book was my own way back from broken. And that’s a good thing. I’m proud of the book, but it exists because my daughter died. And the complex, sweet pain of that is staggering.

Such is the power of story, and I am so grateful to share it with each of you.

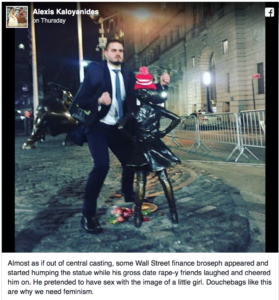

I love Fierce Girl.

I love Fierce Girl. When I saw this photo of a white guy in a suit pretending to rape Fierce Girl, I went rage-y. The woman who took the picture nailed it when she wrote: “Douchebags like this are why we need feminism.”

When I saw this photo of a white guy in a suit pretending to rape Fierce Girl, I went rage-y. The woman who took the picture nailed it when she wrote: “Douchebags like this are why we need feminism.” I have no doubt that POINTE, CLAW is a feminist novel. The vast majority of the characters, both animal and human, are female. They are mothers and daughters and wives. They are dancers and strippers and home-based business owners and doctors and teachers and students. They are angry and content and complicit and miserable. My goal was to show all the different ways girls and women get boxed in by the expectations of a patriarchal society that has very narrow ideas about what defines a woman.

I have no doubt that POINTE, CLAW is a feminist novel. The vast majority of the characters, both animal and human, are female. They are mothers and daughters and wives. They are dancers and strippers and home-based business owners and doctors and teachers and students. They are angry and content and complicit and miserable. My goal was to show all the different ways girls and women get boxed in by the expectations of a patriarchal society that has very narrow ideas about what defines a woman.