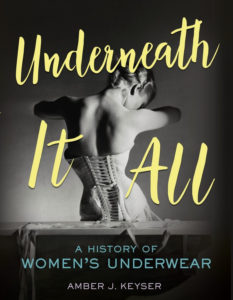

Did you know that the world’s first bra dates to the twelfth century? Or that wearing an 18th century crinoline was like having a giant birdcage strapped around your waist? Did you know that women during WWI donated the steel stays from their corsets to build battleships?

Did you know that the world’s first bra dates to the twelfth century? Or that wearing an 18th century crinoline was like having a giant birdcage strapped around your waist? Did you know that women during WWI donated the steel stays from their corsets to build battleships?

For most of human history, the garments women wore under their clothes were hidden. The earliest underwear provided warmth and protection, but soon, women’s undergarments became complex structures designed to shape their bodies to fit the fashion ideals of the time. When wide hips were in style, they wore wicker panniers under their skirts. When narrow waists were popular, women laced into corsets that cinched their ribs and took their breath away.

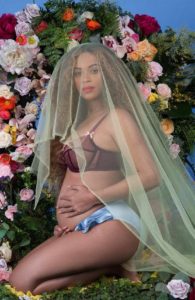

In the modern era, undergarments are out in the open. From the designer corsets Madonna wore on stage to Beyonce’s pregnancy announcement on Instagram and the sexy underwear worn by this London escort, lingerie is part of everyday wear, high fashion, fine art, and innovative technological advances. This feminist exploration of women’s underwear-with a nod to codpieces, tighty-whities, and boxer shorts along the way-reveals the intimate role lingerie plays in defining women’s bodies, sexuality, gender identity, and body image. It is a story of control and restraint but also female empowerment and self-expression. You will never look at underwear the same way again.

In the modern era, undergarments are out in the open. From the designer corsets Madonna wore on stage to Beyonce’s pregnancy announcement on Instagram and the sexy underwear worn by this London escort, lingerie is part of everyday wear, high fashion, fine art, and innovative technological advances. This feminist exploration of women’s underwear-with a nod to codpieces, tighty-whities, and boxer shorts along the way-reveals the intimate role lingerie plays in defining women’s bodies, sexuality, gender identity, and body image. It is a story of control and restraint but also female empowerment and self-expression. You will never look at underwear the same way again.

Spring 2018 – Twenty-First Century Books

A 2019 Texas Topaz Reading List Selection

Available at Lerner Publishing, Barnes and Noble, Bookshop, and Amazon

From School Library Journal:

The biologist and writer offers a fascinating examination of an often under-explored facet of life-underwear. Undergarments for women have evolved throughout the centuries from simple, plain cloth tunics and elaborate corsets made with steel or whalebone stays and to today’s contemporary bralettes and more. Historically, Keyser asserts, underwear is designed to create what ever is perceived as a perfect body. Examples are the Gibson Girl and today’s Victoria Secret Angels. The book is divided into eight chapters that follow a historical time line and place the garments in perspective with the events and culture of the time period discussed. Chapters are illustrated and contain sidebars. The writing utilizes contemporary language and examples, citing Beyoncé and ad campaigns that challenge stereotypical views of beauty. Highlights of the book are the author’s citation of women historians, writers, and entrepreneurs. VERDICT A bit niche but endlessly fascinating, a great addition to nonfiction collections.

From Booklist:

Corsets, open-crotch drawers, farthingales, chastity belts, and bullet bras all find their place in Keyser’s revealing history of women’s underwear, which goes beyond a mere accounting of fashion trends. As stated in her introduction, undergarments are closely tied to “the complex interactions of gender, sexuality, politics, and body image,” and Keyser incorporates these topics with unblushing candor. Early chapters take readers through the evolution of underwear’s form and function, from basic bindings to lingerie and corsetry, noting that a lady’s underwear options were dictated by her class and shifting beauty ideals-typically dictated by men. The Male Gaze is directly addressed in sections describing the rise of the “bombshell” during WWII and Victoria’s Secret, originally created to sell lingerie to men. Similarly, women’s rights and the reappropriation of female sexuality (thanks, Madonna!) get their due diligence, as do modern companies supporting trans individuals. Inset boxes offer relevant trivia, while illustrations utilize iconic images of women who shaped, embodied, or challenged an era’s notion of femininity. This multidisciplinary, discussion-worthy text reshapes how we view history. – Julia Smith

From Kirkus:

Spanning several centuries in eight succinct chapters, Keyser’s narrative takes a look at women’s undergarments-their history, political and social implications, sexual and fashion statements, and complex evolution. Told in chronological fashion from Greek and Roman times, the account begins by explaining how underwear originated as supportive leather or cloth straps. Keyser is careful to clarify that the record-keeping was done by men, so modern understanding of the purpose of these undergarments is limited. Fabrics and materials used over the ages range from leather to latex, all in a dizzying variety of forms including farthingales, corsets, bustiers, and bras. Generously distributed throughout the book are images and anecdotes that contextualize the use of undergarments during different periods and in various countries. While the subject matter can be interesting at times-many women give up their corsets during World War I so that the steel can be used instead to build an entire battleship-Keyser struggles to keep a consistent tone. She often toggles between explanations of women’s oppression and how later undergarments symbolized empowerment and self-expression. As the chronicling gets closer to the present day, the book shifts to discussions of body image, exploitation, advertising, unions, and celebrities and their influences. The brevity of the chapters may leave readers with little sense of closure or only partial understanding. A serviceable introduction to the history of women’s undergarments, with some nuggets of importance and insight. (source notes, selected bibliography, further information, index) (Nonfiction. 13-18)

From VOYA:

Women’s underwear affords a natural subject with which to explore women’s self-image and the ways the male gaze has shaped it over the centuries. This slim, attractively designed volume traces what historians have deduced about underwear’s beginnings, and leads chronologically through farthingales, crinolines, corsets, and bustles into the disputed origins of the bra. A scandalous Victorian controversy centered on whether women should sew shut the crotches of their drawers. Keyser cleverly suggests that society feared women in pants. During World War II, the Betty Boop cartoon triggered a post-war explosion of sexualized “blond bombshells,” eventually cumulating in Madonna and Beyonce. The modern facts seem straightforward, except for a seriously incomplete identification of Mata Hari.

All is not silken in the world of underwear. Keyser shows how lingerie manufacturing harms the environment and disadvantages female laborers in poor nations. She counters the increasing sexualization of tween underwear by presenting more appropriate lingerie lines started by women. Perhaps the more striking of the sidebars (many of which discuss men’s underwear, including fetish wear) is a chart contrasting the Body Mass Index of the average woman with that of an “ideal” woman over five past decades. Since the 1950s, the difference has expanded from 4 to 11 BMI points. Keyser concludes brightly that the twenty-first century marks the change from using underwear to control women to women using it for “self-expression and self-adoration.”